ROODMAN: Appeal to Me – First Trial of a “Replication Opinion”

[This blog is a repost of a blog that first appeared at davidroodman.com. It is republished here with permission from the author.]

My employer, Open Philanthropy, strives to make grants in light of evidence. Of course, many uncertainties in our decision-making are irreducible. No amount of thumbing through peer-reviewed journals will tell us how great a threat AI will pose decades hence, or whether a group we fund will get a vaccine to market or a bill to the governor’s desk. But we have checked journals for insight into many topics, such as the odds of a grid-destabilizing geomagnetic storm, and how much building new schools boosts what kids earn when they grow up.

When we draw on research, we vet it in rare depth (as does GiveWell, from which we spun off). I have sometimes spent months replicating and reanalyzing a key study—checking for bugs in the computer code, thinking about how I would run the numbers differently and how I would interpret the results. This interface between research and practice might seem like a picture of harmony, since researchers want their work to guide decision-making for the public good and decision-makers like Open Philanthropy want to receive such guidance.

Yet I have come to see how cultural misunderstandings prevail at this interface. From my side, there are two problems. First, about half the time I reanalyze a study, I find that there are important bugs in the code, or that adding more data makes the mathematical finding go away, or that there’s a compelling alternative explanation for the results. (Caveat: most of my experience is with non-randomized studies.)

Second, when I send my critical findings to the journal that peer-reviewed and published the original research, the editors usually don’t seem interested ( recent exception).

Seeing the ivory tower as a bastion of truth-seeking, I used to be surprised. I understand now that, because of how the academy works, in particular, because of how the individuals within academia respond to incentives beyond their control, we consumers of research are sometimes more truth-seeking than the producers.

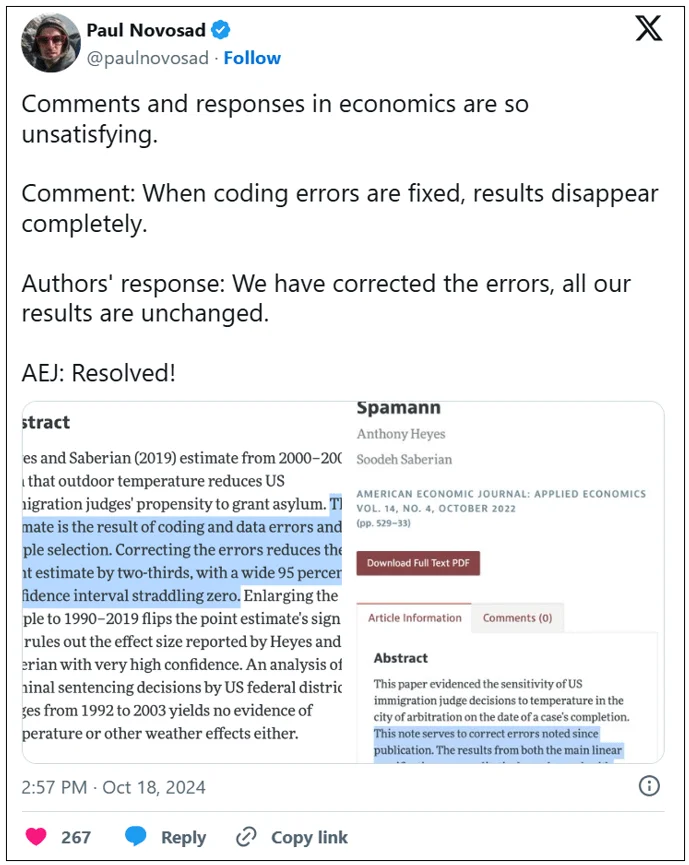

Last fall I read a tiny illustration of the second problem, and it inspired me to try something new. Dartmouth economist Paul Novosad tweeted his pique with economics journals over how they handle challenges to published papers:

As you might glean from the truncated screenshots, the starting point for debate is a paper published in 2019. It finds that U.S. immigration judges were less likely to grant asylum on warmer days. For each 10°F the temperature went up, the chance of winning asylum went down 1 percentage point.

The critique was written by another academic. It fixes errors in the original paper, expands the data set, and finds no such link from heat to grace. In the rejoinder, the original authors acknowledge errors but say their conclusion stands. “AEJ” (American Economic Journal: Applied Economics) published all three articles in the debate. As you can see, the dueling abstracts confused even an expert.

So I appointed myself judge in the case. Which I’ve never seen anyone do before, at least not so formally. I did my best to hear out both sides (though the “hearing” was reading), then identify and probe key points of disagreement. I figured my take would be more independent and credible than anything either party to the debate could write. I hoped to demonstrate and think about how academia sometimes struggles to serve the cause of truth-seeking. And I could experiment with this new form as one way to improve matters.

I just filed my opinion, which is to say, the Institute for Replication has posted it. (Open Philanthropy partly funds them.) My colleague Matt Clancy has pioneered living literature reviews; he suggested that I make this opinion a living document as well. If either party to the debate, or anyone else, changes my mind about anything in the opinion, I will revise it while preserving the history.

Verdict

My conclusion was more one-sided than I had expected. I came down in favor of the commenter. The authors of the original paper defend their finding by arguing that in retrospect they should have excluded the quarter of their sample consisting of asylum applications filed by people from China. Yes, they concede, correcting the errors mostly erases their original finding. But it reappears after Chinese are excluded.

This argument did not persuade me. True, during the period of this study, 2000–04, most Chinese asylum-seekers applied under a special U.S. law meant to give safe harbor to women fearing forced sterilization and abortion in their home country.

The authors seem to argue that because grounds for asylum were more demonstrable in these cases—anyone could read about the draconian enforcement of China’s one-child policy—immigration judges effectively lacked much discretion. And if outdoor temperature couldn’t meaningfully affect their decisions, the cases were best dropped from a study of precisely that connection.

But this premise is flatly contradicted by a study the authors cite called “Refugee Roulette.” In the study, Figure 6 shows that judges differed widely in how often they granted asylum to Chinese applicants. One did so less than 5% of the time, another more than 90%, and the rest were spread evenly between. (For a more thorough discussion, read sections 4.4 and 6.1 of my opinion.)

Thus while I do not dispute that there is a correlation between temperature and asylum grants in a particular subset of the data, I think it is best explained by p-hackin g or some other form of “filtration,” in which, consciously or not, researchers gravitate toward results that happen to look statistically significant. (In fairness, they know that peer reviewers, editors, and readers gravitate to the same sorts of results, and getting a paper into a good journal can make a career.)

The nature of the defense raises a question about how the journal handled the dispute. It published the original authors’ rejoinder as a Correction . Yet, while one might agree that it is better to exclude Chinese from the analysis, I think their inclusion in the original was not an error, and therefore their exclusion is not a correction. Thus, one way the journal might have headed off Novosad’s befuddlement would have been by insisting that Corrections only make corrections.

What’s wrong with this picture?

To recap:

– Two economists performed a quantitative analysis of a clever, novel question.

– It underwent peer review.

– It was published in one of the top journals in economics. Its data and computer code were posted online, per the journal’s policy

– Another researcher promptly responded that the analysis contains errors (such as computing average daytime temperature with respect to Greenwich time rather than local time), and that it could have been done on a much larger data set (for 1990 to ~2019 instead of 2000–04). These changes make the headline findings go away.

– After behind-the-scenes back and forth among the disputants and editors, the journal published the comment and rejoinder.

– These new articles confused even an expert.

– An outsider (me) delved into the debate and found that it’s actually a pretty easy call.

If you score the journal on whether it successfully illuminated its readership as to the truth, then I think it is kind of 0 for 2.

[Update: I submitted the opinion to the journal, which promptly rejected it. I understand that the submission was an odd duck. But if I’m being harsh I can raise the count to 0 for 3.]

That said, AEJ Applied did support dialogue between economists that eventually brought the truth out. In particular, by requiring public posting of data and code (an area where this journal and its siblings have been pioneers), it facilitated rapid scrutiny.

Still, it bears emphasizing:For quality assurance, the data sharing was much more valuable than the peer review. And, whether for lack of time or reluctance to take sides, the journal’s handling of the dispute obscured the truth.

My purpose in examining this example is not to call down a thunderbolt on anyone, from the Olympian heights of a funding body. It is rather to use a concrete story to illustrate the larger patterns I mentioned earlier.

Despite having undergone peer review, many published studies in the social sciences and epidemiology do not withstand close scrutiny. When they are challenged, journal editors have a hard time managing the debate in a way that produces more light than heat.

I have critiqued papers about the impact of foreign aid, microcredit, foreign aid, deworming, malaria eradication, foreign aid, geomagnetic storm risk, incarceration, schooling, more schooling, broadband, foreign aid, malnutrition, ….

Many of those critiques I have submitted to journals, typically only to receive polite rejections. I obviously lack objectivity. But it has struck me as strange that, in these instances, we on the outside of academia seem more concerned about getting to the truth than those on the inside. Sometimes I’ve wished I could appeal to an independent authority to review a case and either validate my take or put me in my place.

That yearning is what primed me to respond to Novosad’s tweet by donning the robe of a judge myself. (I passed on the wig.)

I’ve never edited a journal, but I’ve talked to people who have, and I have some idea of what is going on. Editors juggle many considerations besides squeezing maximum truth juice out of any particular study. Fully grasping a replication debate takes work—imagine the parties lobbing 25-page missives at each other, dense with equations, tables, and graphs—and editors are busy.

Published comments don’t get cited much anyway, and editors keep an eye on how much their journals get cited. They may also weigh the personal costs for the people whose reputations are at stake. Many journals, especially those published by professional associations, want to be open to all comers—to be the moderator, not the panelist, the platform, not the content provider.

The job they set for themselves is not quite to assess the reliability of any given study (a tall order) but to certify that each article meets a minimum standard, to support the collective dialogue through which humanity seeks scientific truth.

Then, too, I think journal editors often care a lot about whether a paper makes a “contribution” such as a novel question, data source, or analytical method. Closer to home, junior editors may think twice before welcoming criticism that could harm the reputation of their journal or ruffle the feathers of more powerful members of their flock. Senior editors may have gotten where they are by thinking in the same, savvy way.

Modern science is the best system ever developed for pursuing truth. But it is still populated by human beings ( for how much longer?) whose cognitive wiring makes the process uncomfortable and imperfect. Humans are tribal creatures—not as wired for selflessness as your average ant, but more apt to go to war than an eel or an eagle.

Among the bits of psychological glue that bind us are shared ideas about “is” and “ought.” Imperialists and evangelists have long influenced shared ideas in order to expand and solidify the groups over which they hold sway. The links between belief, belonging, and power are why the notion that evidence trumps belief was so revolutionary when the Roman church sent Galileo to his death, and why the idea, despite making modernity possible, remains discomfiting to this day.

The inefficiency in pursuing truth has real costs for society. Some social science research influences decisions by private philanthropies and public agencies, decisions whose stakes can be measured in human lives, or in the millions, billions, even trillions of dollars. Yet individual studies receive perhaps hundreds of dollars worth of time in peer review, and that within a system in which getting each paper as close as possible to the truth is one of several competing priorities.

Making science work better is the stuff of metascience, an area in which Open Philanthropy makes grants. It’s a big topic. Here, I’ll merely toss out the idea that if these new-fangled replication opinions were regularly produced, they could somewhat mitigate the structural deprecation of truth-seeking.

On the demand side—among decision-makers using research—replication opinions could improve the vetting of disputed studies, while efficiently targeting the ones that matter most. (Related idea here.)

On the supply side, a heightened awareness that an “appeals court” could upstage journals in a role laypeople and policymakers expect them to fill—performing quality assurance on what they publish—could stimulate the journals to handle replication debates in a way that better serves their readers and society.

Reflections on writing the replication opinion

Writing a novel piece led me to novel questions. To prepare for writing my opinion, I read about how judges write theirs. Judicial opinions usually have a few standard sections. They review the history of the case (what happened to bring it about, what motions were filed); list agreed facts; frame the question to be decided; enunciate some standard that a party has to meet, perhaps handed down by the Supreme Court; and then bring the facts to the standard to reach a decision.

Could I follow that outline? Reviewing the case history was easy enough. I had the papers and could inventory their technical points. The data and computer code behind the papers are on the web, so I could rerun the code and stipulate facts such as that a particular statistical procedure applied to a particular data set generates a particular output.

Figuring out what I was trying to judge was harder. Surely it was not whether, for all people, places, and times, heat makes us less gracious. Nor should I try to decide that question even in the study’s context, which was U.S. asylum cases decided between 2000 and 2004.

Truth in the social sciences is rarely absolute. We use statistics precisely because we know that there is noise in every measurement, uncertainty in every finding. In addition, by Bayes’ Rule, the conclusions we draw from any one piece of evidence depend on the prior knowledge we bring to it, which is shaped by other evidence.

Someone who has read 10 ironclad articles on how temperature affects asylum decisions should hardly be moved by one more. Yet I think those 10 other studies, if they existed, would lie beyond the scope of this case.

That means that my replication opinion is not about the effects of temperature on behavior in any setting. It’s more meta than that. It’s about how much this new paper should shift or strengthen one’s views on the question.

After reflecting on these complications, here is what I decided to decide: to the extent that a reasonable observer updated their priors after reading the original paper, how much should the subsequent debate reverse or strengthen that update?

My judgment need not have been binary. Unlike a jury burdened with deciding guilt or innocence, a replication opinion can come down in the middle, again by Bayes’ Rule. Sometimes there is more than one reasonable way to run the numbers and more than one reasonable way to interpret the results.

I sought rubrics through which to organize my discussion—both to discipline my own reasoning and to set precedents, should I or anyone else do this again. I borrowed a typology developed by former colleague Michael Clemens of the varieties of replication and robustness testing, as well as a typology of statistical issues from Shadish, Cook, and Campbell.

And I made a list of study traits that we can expect to be associated, on average, with publication bias and other kinds of result filtration. For example, there is evidence that in top journals, statistical results from junior economists, who are running the publish-or-perish gauntlet toward tenure, are more likely to report results that just clear conventional thresholds for statistical significance. That is consistent with the theory that the researchers on whom the system’s perverse incentives impinge most strongly are most apt to run the numbers several ways and emphasize the “significant” runs in their write-ups.

One tricky issue was how much I should analyze the data myself. The upside could be more insight. The downside could be a loss of (perceived) objectivity if the self-appointed referee starts playing the game. Wisely or not, I gave myself some leeway here. Surely real judges also rely on their knowledge about the world, not just what the parties submit as evidence.

For example, in addition to its analysis of asylum decisions, the original paper checks whether the California parole board was less likely to grant parole on warmer days in 2012–15. Partly because the critical comment did not engage with this side-analysis, I revisited it myself. I transferred it to the next quadrennium, 2016–19, while changing the original computer code as little as possible. (Here, too, the apparent impact of temperature went away.)

Closing statement

The stakes in this case are probably low. While the question of how temperature affects human decision-making links broadly to climate change, and the arbitrariness of the American immigration system is a serious concern, I would be surprised if any important policy decision in the next few years turns on this research.

But the case illustrates a much larger problem. Some studies do influence important decisions. That they have been peer-reviewed should hardly reassure. Judicious post-publication review of important studies, perhaps including “replication opinions,” can give decision-makers with real dollars and real livelihoods on the line a clearer sense of what the data do and do not tell us.

Unfortunately, powerful incentives within academia, rooted in human nature, have generally discouraged such Socratic inquiry.

I like to think of myself as judicious. As to whether I’ve lived up to my self-image in this case, I will let you be the judge. At any rate, I figure that in the face of hard problems, it is good to try new things. We will see if this experiment is replicated, and if that does much good.

David Roodman is Senior Advisor at Open Philanthropy. He can be contacted at david@davidroodman.com

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

Like Loading…