Navigating Open scholarship for neurodivergent researchers

Introducing the Neurodiversity group at FORRT.

Navigating Open scholarship for neurodivergent researchers

Who we are and why is this important?

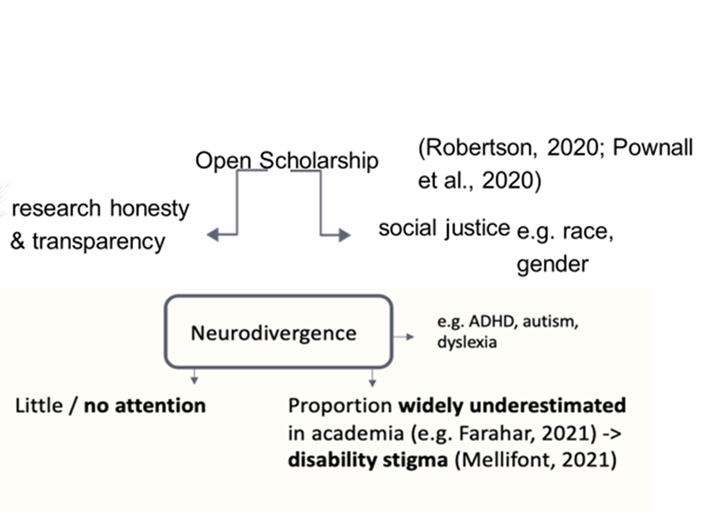

In academia, there has been much discussion about how open scholarship can benefit marginalised voices (e.g. Robertson, 2020; Pownall et al., 2020). However, neurodivergent individuals (e.g. dyslexic, autistic, ADHD) have received little attention. According to the Higher Education Statistics Agency, only 2.2% in 2003/04, 3.9% in 2012/13 to 5.5% in 2019/2020 of staff at universities in the UK disclosed having a physical or neurological disability. However, the true figures are likely to be higher. Despite increased coverage and interest regarding disability issues in academia, concerns regarding negative perceptions of disability disclosure remain. More open discussions are taking place about the lived experiences of disabilities and chronic illnesses, as people with disability are becoming less stigmatised, leading to more disclosures being discussed. However, there is still a question being asked: ‘where are the disabled academics?’ (We are here but you don’t see us!).

Disability? How do you have a disability? You do not have a deficit with your body, you can still function in society, earn a living and participate in community life. Disability is portrayed as a personal tragedy, with some heroic individuals “overcoming” their terrible handicap. So how are you disabled? The answer is that not all disabilities are visible. The relative proportion of disabled academics is widely underestimated (e.g. Farahar, 2021), likely due to the stigma attached to the concept of disability (Mellifont, 2021). In addition, there are too many assumptions about disability being a physical or intellectual impairment with no discussion on difficulties regarding cognition and mental health. This discussion also fails to encapsulate that the range of difficulties people face may be connected to an individual’s neurodevelopmental characteristics (Singer, 2017). This is in spite of the fact that there are conditions that are described by psychologists as disabling but people with these conditions are treated as if they are not disabled. This is the ‘neurodiverse’ group.

Neurodiversity is the non-pathological variation in the human brain regarding sociability, learning, attention, mood and other mental functions at a group level (Singer, 2017). An individual is neurodivergent if their neurology diverges from that of the neurological majority. Neurodiversity is critically relevant to the social sciences as it discusses the diverse cognitive behaviours forming the foundations of what it means to be unique and human. Importantly, the neurodiversity movement questions the assumption that all humans must conform to the same expectations in order to flourish.

So, you may still be wondering how neurodivergent individuals are disabled? The labelling of disability is a personal matter. It depends on what models we use to interpret it. Under the medical model, disability is portrayed as a flaw, weakness or a biological limitation of the individual. Put simply, it is a personal tragedy that was inflicted on you. Disability under the social theory of disability is defined not as a personal tragedy but as the result of barriers – environmental and social practices that disable, as opposed to enabling, the individual. In addition, the social model makes the distinction that an impairment is a property of an individual body, while disability is a social process. However, it is important to remember that both models are not mutually exclusive, but are required to be used together to open a constructive dialogue between able-bodied and disabled individuals, even among disabled individuals. The important message is that disabilities are dynamic and reasonable adjustments should be made for all groups.

In today’s academic environment, the economic and political system of universities, among many other industries, focus on productivity and profit. As a result, measures that focus on productivity and profit such as standards, norms, league tables, achievements and publications are becoming more and more important. Health and wellbeing and slow science are becoming less important, despite the fact that slow science and resting are important for creativity, critical thinking and understanding data, three crucial components to help accumulate knowledge. As a result of this development, burnout becomes more common and this is more prevalent among people with disabilities (Burns et al., 2021).

People with disabilities are more likely to be excluded from the academic workforce with its demands for speed, efficiency and productivity, leading to normalised, ingrained and internalised ableism to an extent that they desire to be able-bodied. As a result of this exclusion, able-bodied individuals may believe that disabled individuals do not contribute to the productivity of the community and argue that their unemployment is the ‘fate of the idle’ (Singer, 2017). This means that in academia and industry, people with disabilities become oppressed, mocked, ridiculed and perceived as a nuisance.

Many gatekeepers determine whether an individual is neurodivergent and these processes are driven by individuals who are neurotypical. As a result, referral time for these services vary widely, from 4 weeks to 201 weeks within the UK (Lloyd, 2019) and if a person does not fit the criteria, the individual can be ignored and may not receive the much-needed help that they require. This can lead to poor self-esteem, unemployment (e.g. around 22% in autistic people are in any type of employment; see Figure 2 in fact sheet). As a result, neurodivergent individuals may blame themselves for the difficulties they encounter, as opposed to the barriers that society has placed on them.

Despite this, people of different neurodivergent conditions or families of the people with the conditions have begun meeting and talking to each other about their experiences and one common shared experience is a history of misinterpretation and mistreatment by the dominant neurotypical cultures and its institutions such as academia. As a result of centuries of oppression of disabled people worldwide and a hyper-normalised environment, in addition to seeing the disproportionate impact of the coronavirus pandemic on disabled students (see this amazing paper by Dr Joanna Zawadka), many neurodivergent and disabled staff feel discouraged in an environment that should aim to support them. They do not feel like they belong, their differences are seen as an impairment and their voice does not seem to matter. They do not see themselves represented in psychological science, academia, business, teaching or elsewhere.

We are a group of early-career neurotypical and neurodivergent researchers that are a part of the Framework of Open Reproducible Research and Training (FORRT) community, aiming to make academia and the open scholarship community more open to neurodiversity. Everyone, no matter what they identify with, is welcome in this group. We aim to discuss how open scholarship can be intersected with the neurodiversity movement, and emphasise how differences should be highlighted and accepted, whilst supporting the idea of accessibility. Our neurodiversity team is a group that currently consists of individuals that have autism, dyspraxia/DCD, speech-language differences, ADHD, dyslexia, or are neurotypical allies. If you have these or other neurominorities and wish to be part of the team, you are more than welcome to join!

What do we want?

We want academia and open scholarship not to be covertly homophobic, racist, sexist and ableist. However, by attempting to adapt and work within the existing defined rules of academia and its power structures, what we do is reinforce that system, irrespective of intentions. Lorde (2018) illustrates this well in the metaphor: the master’s tools (i.e. the dynamics, language, and conceptual framework that create and maintain social inequities) never serve to dismantle the master’s house, but somehow end up building another extension of that mansion. Similarly, the fundamental assumption under the medical model of disability serves to both disempower the individual and strengthen societal perception that the neurodivergent person is the problem. Thus, we need lasting, sustainable, and widespread empowerment that can be obtained by making and propagating the shift from the medical to the social model, or use both in order to encourage a constructive dialogue. Put simply, in order to fulfil our potential, we as neurodivergent people cannot say that there is something wrong with us, and we must use the tools of the social model to temper or remove barriers provided by the medical model.

According to Feminist Standpoint theory (Harding, 1992; Pohlhaus, 2002), it is important that we empower under-represented and marginalised voices in knowledge production, and draw upon the lived experience when designing for under-represented voices. However, this is not possible, as we still follow psychology’s positivist (i.e., all authentic knowledge is scientific knowledge) tradition; this assumes that there is a fundamental truth of human diversity and that scientists should be objective. However, the research conducted on neurominorities is marred by the fact scientists are like everyone else. We are humans with different political views and lived experiences as well as biases (e.g. confirmation bias), which affect the questions that are asked and influence researchers’ degrees of freedom. Therefore, studies into neurodiversity are undertaken within structures that are characterised by power relationships, where colour, gender and neurological makeup are in no way neutral. This leads to neurodivergent individuals being treated as an _object _of the conversation, rather than the subject. This is analogous to the way the Eastern Societies and their members were treated by Western Researchers in the mid and late 20th Century (see Said’s Orientalism for further discussion; Said, 1976). “The Orient” was othered, misunderstood and seen as inferior, which led to a very skewed depiction which reflected Western biases. In post-colonial times, our awareness of power relations is, at least in some academic publications, greater than before. However, in the case of neurodiversity, there has been little change as most studies in the area are still conducted by those in possession of greater social power, with little input from neurodivergent researchers. This approach is not only patronising, but very dangerous as it will take centuries to counteract the discrimination it produces.

The power structure that dominates psychology and social sciences is from white, male and able-bodied people who treat neurodivergent people as an object of the conversation, not the subject. As argued by Jackson (1998, p.8), “Each person is at once a subject for himself or herself - a _who _- and an object for others - a what. And though individuals speak, act, and work toward belonging to a world of others, they simultaneously strive to experience themselves as world makers”. Once we consider that scientists are human, and neurodivergent people can be included in this research, then we can co-create projects that allow us to discover the truth about diversity from different perspectives. This is more commonly discussed in qualitative research but rarely even considered in quantitative research. In addition, with different perspectives, there is an emphasis on moving away from the typical White, Educated, Industrial, Rich, Democratic (WEIRD) samples that account for 80% of study samples but only 12% of the world population, despite the fact that this movement does not acknowledge the neurodiversity movement or neurominorities (e.g. autistic, ADHD, dyslexic). In addition, there is a lack of patient involvement in how to make the research more likely to improve the quality of life of neurodivergent people. The need to address this issue and to ensure disabled and marginalised individuals are directly included in research and policy-making decisions that affect them can be expressed by the commonly used slogan “Nothing about us without us”. Emancipatory and/or participatory approaches such as participatory action research (e.g. Bertilsdotter-Rosqvist et al., 2019; Fletcher-Watson et al., 2018; Grant & Kara, 2021; Leadbitter et al., 2021; Strang et al., 2019; Strang et al., 2021) have considerable potential for facilitating this type of collective knowledge creation and driving social change that benefits neurodivergent people in areas that may contrast with many mainstream research approaches.

A recent movement has become important in education: open scholarship. This reflects the idea that knowledge of all kinds should be openly shared, transparent, rigorous, reproducible, replicable, accumulative, and inclusive (allowing for all knowledge systems). Open scholarship includes all activities that are not solely limited to research such as teaching and pedagogy. One key foundation of open scholarship is accessibility, a key facet that also belongs to the neurodiverse movement (e.g. Brown & Leigh, 2018; Brown et al., 2018). Accessibility and inclusion is where your content, activities and all their components are accessible to all people with disabilities, learning differences, mental health conditions or other health conditions that may affect their learning or engagement with the materials and activities, research activities, clinical training, and teaching (Victor et al., 2021a). It highlights the importance of embracing diversity and making everyone feel welcome and valued (see information sheet). Discussions have been, however, scarce regarding not only how open scholarship can advance the neurodiverse movement, but also how it can benefit from it. It is thus a priority to build community to discuss how the neurodiversity movement can be included in open scholarship, as the lived experience of neurodivergent individuals (including encountered barriers) may help to enhance accessibility, allowing open scholarship to be truly open (Whitaker & Guest, 2020). This in turn may help to dismantle the harmful stereotypes about disabled individuals (Devendorf et al., 2021), providing more specific provisions for neurodivergent and/or disabled researchers (e.g. virtual conferences; see Levitis et al., 2021). Furthermore, including this population in academia will help promote work-life balance, by denormalising overwork and practices that lead to burnout.

There has been a recent shift towards the use of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) (i.e., an approach to teaching highlighting that academics/tutors should be proactively, not reactively, inclusive by making adjustments to their teaching without students having to disclose their disability to student disability services) in higher education (Burgstahler & Cory, 2010). UDL has several benefits: by offering a more flexible and inclusive practice, there is no need to disclose one’s disability, irrespective of student status (Clouder et al., 2020). In addition, making the assumption about the student’s intention based on your interpretation of their behaviour can be damaging for neurodivergent students’ self-esteem. University staff should recognise the different manners in which students may communicate and contribute, whilst being open to collaborating with students to find suitable approaches. Put simply, it can be described as neurodiversity involvement for pedagogy.

In addition, UDL allows students to engage in the material that best suits their learning. Traditionally, university students are assessed through essays/ dissertations, group/individual presentations or examinations with very little discussion but neurodivergent students may find these types of assignments challenging that otherwise may succeed. UDL encourages educators to examine the students’ strengths, as opposed to weaknesses and allows students to have more choice. Learners could do a recorded presentation, as opposed to presenting in a group or present the skills they have acquired on the course in a different form that may suit them better. This would benefit the students in terms of better preparation for employment, by focusing on the student’s ability and professional values, as opposed to the challenges. This approach is also fully aligned with the UK Professional Standards Framework in Higher Education (UKPSF) as it facilitates educators’ continuous development (A5), focuses on respecting individual learners and diverse learning communities (V1), promotes participation in higher education and equality of opportunity for learners (V2) and acknowledges the wider context in which higher education operates recognising the implications for recognising the implications for professional practice (V4). Another example is that attendance should not be used as a marker of class engagement, as there are several variables that predict class attendance (e.g. keeping pace with other students, attentional demands, and attendance being socially impossible). At the start of class, educators should signpost the expected outline and inform students before an activity is finished or changed. This lack of physical attendance and/or inability to follow attentional cues is not evidence of a lack of engagement but that students may engage in ways that are not expected and we should meet them where they are now, as opposed to where we expect them to be.

An important core property of UDL is to provide choice to allow students to develop agency in their own learning. Lecturers may feel that academic standards will not be maintained or students will not learn the learning outcomes but this choice aims to remove structural barriers that are faced when perhaps making a specific activity unnecessarily difficult, as opposed to reducing the academic level. For instance, lecture capture allows the student to learn in an environment that suits them and to learn at their own pace. Over decades, lecturers have questioned the effectiveness of lecture capture (Nordmann et al., 2021), but students such as dyslexic students, who otherwise struggled, may engage with learning and develop at their own speed (Nightingale et al., 2019). Rather than develop concerns on whether students will continue to engage, UDL offers students an opportunity to develop agency in their learning, a goal that lecturers should encourage. And applied more broadly to the academic employees’ relationships, UDL can also improve the academic culture, providing academic workers with opportunities to engage in their trade in a way that fits their neurocognitive style. Last but not least, UDL promotes and facilitates social justice and equality.

Finally, we want academia to approach neurodiversity in the same way that true cosmopolitans approach cultural diversity. We want academics to reject the idea that the lived experiences of neurominorities such as dyslexia, autism, ADHD, which differs from the neuromajority, should be pathologised. Rather, these experiences should be accepted as fundamental to the human experience, to allow us to have different perspectives to understand what it means to be human. As a result, by considering this perspective, ‘‘our strengths and deficits will shape, not deny, our humanity’ (Grinker, 2010, p.173).

Put simply, our team wants people in academia and the open scholarship community to understand that: “Being disabled does not make a person any less of a scientist. Actively listen to your students and/or peers if they disclose their disabilities, as they have entrusted you with sharing this important part about themselves. **If you are in a position of power and a disabled person asks for accommodations, give it to them. **Learn to recognise that disabilities are unique and dynamic. Ultimately, we should strive for universal design, of both our workspaces and pedagogy, as this gives everybody the best chance to fully be themselves and blossom in science” ( Middleton, 2021).

Our plans

Our overall aims are to: reduce the stigma neurodivergent individuals face by raising awareness of the contributions neurodivergent researchers have made, encourage neurodivergent researchers that there is no need to mask or hide our differences, and show that neurodiversity is an asset to open scholarship and academia. Open scholarship, like psychological science, benefits from neurodiversity and disabled perspectives, which have been growing in the past decade (e.g. Chown et al., 2017; Gillespie-Lynch et al., 2017; Grant & Kara, 2021; Kapp, 2020).

Currently, we are in the initial stages of creating a database of papers written by neurodivergent researchers. This will be a comprehensive crowd-sourced database of research written by neurodivergent researchers with the aim to allow educators to diversify their syllabi to include neurodivergent researchers to help counteract the bias towards able-bodied researchers. This database will help students feel that they can belong in academia, and that neurodivergent or disabled people can have some important strengths in research contexts (Grant & Kara, 2021). This project aims to be a “living“ resource, which will be regularly updated to include new studies authored by neurodivergent researchers.

In addition, we will engender a survey which will be similar to Victor et al. (2021b) and Devendorf et al. (2021). Their surveys investigated prevalence of lived experience, discussed the lived experiences and stigma (e.g. attitudes towards self-relevant research, help-seeking, disclosure) of mental health challenges among applied psychology researchers. The neurodiversity survey will detail the proportion of neurodivergent students and researchers (e.g. undergraduate students, graduate students, post-doctoral researchers) from different countries and different disciplines. It will investigate experiences in academia, possible concerns and barriers (e.g. external stigma, self stigma and difficulties in help-seeking) of neurodivergent students and researchers. In addition, we will discuss attitudes towards the neurodiversity movement, open scholarship, and the intersectionality between neurodiversity and open scholarship. We believe our work will improve neurodiverse representation and awareness. More importantly, we hope our work will also promote the inclusion of neurodiversity within the scientific community and the next generation of neurodivergent scientists. By including a neurodiverse population, “we have a huge opportunity to not only advance our science but also to equitably serve all of humanity” (Ghai, 2021, p2). Thus, we can encourage ourselves to broaden our minds and to truly be “open” in open scholarship.

Finally, we are also currently planning a manuscript that will take the form of a position statement, detailing how neurodiversity and open scholarship can benefit from each other. With these additional resources to combat the biases, prejudices and misconceptions of disability, you may be surprised what we can bring to the table and we hope these resources can enable us to do just that.

Join us!

We need to discuss the challenges faced by neurodivergent people, so they can feel seen. It is a wonderful experience to be seen and heard. We feel sad that not all neurodivergent people will encounter the same privileges that we have encountered. They feel these things so hard and this impacts their mental health, and in turn, leads to very upsetting ends. Neurodivergent people have been marginalised in so many ways that we have missed so many opportunities to make their lives that much better. We cannot change what has happened in the past; however, we hope that the resources we create will help improve representation early in students’ careers, so then they can hold their head high and smile, knowing they do not need to mask anymore. Also, they can feel proud that they can be themselves, achieve things with the correct reasonable adjustments and be treated as an equal, not an inferior. Put simply, we would like ally neurotypical academics of the neurodiverse movement and disabled academics to join us at FORRT, so we can provide “more effective support…[including] specific provisions for disabled researchers, online conferences and the ability to work from home” (Niedernhuber et al., 2021 p.34). These provisions need to continue post-COVID-19 pandemic because we cannot return back to normalcy. Not because it is not possible, but because the conversation about disability, race and gender has truly started and we are not letting this conversation end until everyone feels included in their environment. We want everyone not to just survive, but to thrive and flourish in their respective environment.

History of Team-Neurodiversity

This project began on the 24th June 2021 meeting of the Society for the Improvement of Psychological Science in a roundtable discussion, “How can open scholarship support evidence-based learning in people with neurodiverse conditions?” led by Dr. Tamara Kalandaze and Dr. Mahmoud Elsherif. During this roundtable discussion, Dr. Amélie Gourdon-Kanhukamwe attended this discussion. As a result of a fruitful discussion, an initial framework was developed that led to a discussion about how open scholarship and neurodiversity intersect, and on the 28th of June 2021, Team Neurodiversity was created. However, Team Neurodiversity did not have a home to discuss open scholarship and neurodiversity topics. The Framework for Open and Reproducible Research Training (FORRT) kindly offered us a base so we could establish ourselves and become a tour de force in this area. Although it started with five members, it has grown to a smashing total of 56 members based in more than 8 countries and is still increasing! The team has finished working on a database on neurodivergent scholars; a blog about open scholarship and its intersection with neurodiversity, which has been expanded to a position statement manuscript; a manuscript accepted in the British Psychological Society Cognitive Psychology Bulletin and a manuscript accepted in Association in Psychological Science. Currently, we are developing a survey to assess masking and neurodivergence in academia and the convergence between open scholarship values and neurodivergent values. We have a rotating leadership team which changes every six months. To promote diverse and inclusive leadership, anyone can put themselves forward for this role, regardless of their experience. The current team leaders are Magdalena Grose-Hodge and Bethan Iley. Thank you to our previous team leaders: Amélie Gourdon-Kanhukamwe, Flávio Azevedo, and Mahmoud Elsherif.

References

Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, H., Kourti, M., Jackson-Perry, D., Brownlow, C., Fletcher, K., Bendelman, D., & O’Dell, L. (2019). Doing it differently: emancipatory autism studies within a neurodiverse academic space. Disability & Society, 34(7-8), 1082-1101. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1603102

Botha M. (2021). Academic, Activist, or Advocate? Angry, Entangled, and Emerging: A Critical Reflection on Autism Knowledge Production. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 727542. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.727542

Brown, N., & Leigh, J. (2018). Ableism in academia: where are the disabled and ill academics?. Disability & Society, 33(6), 985-989. https:/doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1455627

Brown, N., Thompson, P., & Leigh, J. S. (2018). Making academia more accessible. Journal of Perspectives in Applied Academic Practice, 6(2), 82-90. https://doi.org/10.14297/jpaap.v6i2.348

Burns, K. E., Pattani, R., Lorens, E., Straus, S. E., & Hawker, G. A. (2021). The impact of organizational culture on professional fulfillment and burnout in an academic department of medicine. PloS one, 16(6), e0252778. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252778

Burgstahler, S. E., & Cory, R. C. (2010). Universal design in higher education: From principles to practice. Harvard Education Press.

Chown, N., Robinson, J., Beardon, L., Downing, J., Hughes, L., Leatherland, J., … & MacGregor, D. (2017). Improving research about us, with us: a draft framework for inclusive autism research. Disability & society, 32(5), 720-734.https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1320273

Clouder, L., Karakus, M., Cinotti, A., Ferreyra, M. V., Fierros, G. A., & Rojo, P. (2020). Neurodiversity in higher education: A narrative synthesis. Higher Education, 80(4), 757-778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00513-6

Devendorf, A., Victor, S. E., Rottenberg, J., Miller, R., Lewis, S., Muehlenkamp, J. J., & Stage, D. L. (2021, November 7). Stigmatizing our own: Self-relevant research is common but frowned upon in clinical, counseling, and school psychology. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/szg5d

Farahar, C. (2021, May 13) How can we enable neurodivergent academics to thrive? LSE Higher Education Blog.

Fletcher-Watson, S., Adams, J., Brook, K., Charman, T., Crane, L., Cusack, J., … & Pellicano, E. (2019). Making the future together: Shaping autism research through meaningful participation. Autism, 23(4), 943-953. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318786721

Gillespie-Lynch, K., Kapp, S. K., Brooks, P. J., Pickens, J., & Schwartzman, B. (2017). Whose expertise is it? Evidence for autistic adults as critical autism experts. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 438. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00438

Grant, A., & Kara, H. (2021). Considering the Autistic advantage in qualitative research: the strengths of Autistic researchers. Contemporary Social Science, 16(5), 589-603. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2021.1998589

Grinker R R. (2010). Commentary: On being autistic and social. Ethos, 38 (1), 172-8.

Harding, S. (1992). Rethinking standpoint epistemology: What is" strong objectivity?". The Centennial Review, 36(3), 437-470. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23739232

Jackson, M. (1998) Minima Ethnographica: Intersubjectivity and the Anthropological Project. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kapp, S. K. (2020). Autistic community and the neurodiversity movement: Stories from the frontline. Springer Nature.

Leadbitter, K., Buckle, K. L., Ellis, C., & Dekker, M. (2021). Autistic self-advocacy and the neurodiversity movement: Implications for autism early intervention research and practice. Frontiers in Psychology, 782.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635690

Levitis, E., Van Praag, C. D. G., Gau, R., Heunis, S., DuPre, E., Kiar, G., … & Maumet, C. (2021). Centering inclusivity in the design of online conferences—An OHBM–Open Science perspective. GigaScience, 10(8), giab051.https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giab051

Lloyd, T. (2019). An audit of ADHD service provision for adults in England. https://www.adhdfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Takeda_Will-the-doctor-see-me-now_ADHD-Report.pdf

Lorde, A. (2018). The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. Penguin UK.

Mellifont, D. (2021). Ableist ivory towers: a narrative review informing about the lived experiences of neurodivergent staff in contemporary higher education. Disability & Society, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2021.1965547

Niedernhuber, M., Haroon, H., & Brown, N. (2021). Disabled scientists’ networks call for more support. Nature, 591(7848), 34-34. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-00544-8

Nightingale, K. P., Anderson, V., Onens, S., Fazil, Q., & Davies, H. (2019). Developing the inclusive curriculum: Is supplementary lecture recording an effective approach in supporting students with Specific Learning Difficulties (SpLDs)?. Computers & Education, 130, 13-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.11.006.

Nordmann, E., Clark, A., Spaeth, E., & MacKay, J. R. (2021). Lights, camera, active! appreciation of active learning predicts positive attitudes towards lecture capture. Higher Education, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00674-4

Pohlhaus, G. (2002). Knowing communities: An investigation of Harding’s standpoint epistemology. Social epistemology, 16(3), 283-293. https://doi.org/10.1080/0269172022000025633

Said, E.W. (1978). Orientalism. New York: Pantheon

Singer, J. (2017). NeuroDiversity: The Birth of an Idea. Amazon Kindle eBook, self-published.

Strang, J. F., Klomp, S. E., Caplan, R., Griffin, A. D., Anthony, L. G., Harris, M. C., … & van der Miesen, A. I. (2019). Community-based participatory design for research that impacts the lives of transgender and/or gender-diverse autistic and/or neurodiverse people. Clinical practice in pediatric psychology, 7(4), 396 .https://doi.org/10.1037/cpp0000310

Strang, J. F., Knauss, M., van der Miesen, A., McGuire, J. K., Kenworthy, L., Caplan, R., … & Anthony, L. G. (2021). A clinical program for transgender and gender-diverse neurodiverse/autistic adolescents developed through community-based participatory design. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 50(6), 730-745. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2020.1731817

Victor, S. E., Schleider, J. L., Ammerman, B. A., Bradford, D. E., Devendorf, A., Gruber, J., … Stage, D. L. (2021a, July 12). Leveraging the Strengths of Psychologists with Lived Experience of Psychopathology. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ksnfd

Victor, S. E., Devendorf, A., Lewis, S., ROTTENBERG, J., Muehlenkamp, J. J., Stage, D. L., & Miller, R. (2021b, July 12). Only human: Mental health difficulties among clinical, counseling, and school psychology faculty and trainees. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/xbfr6